Reflections on Peter Watkins’ exhibition at Open Eye Gallery, 2016

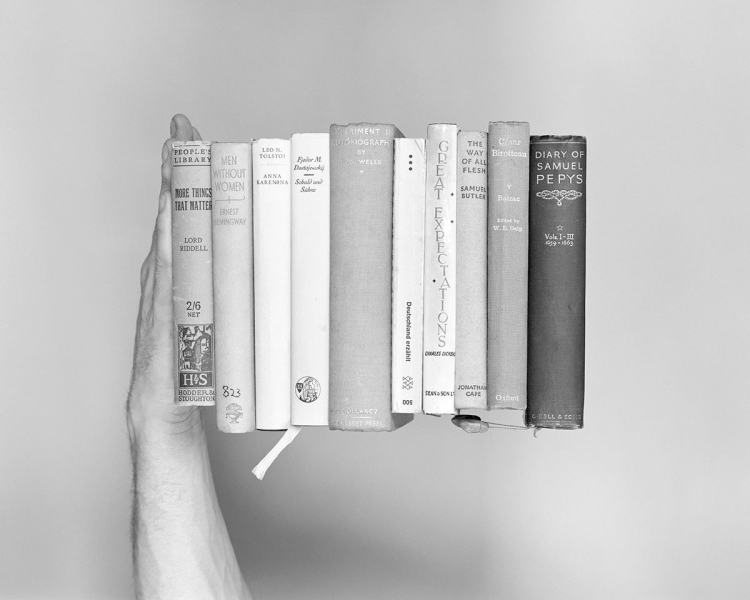

In Gallery One the image that we first see is a set of books held in mid-air like a magic trick. Peter Watkins’ photographs are displayed within frames and placed on a wooden L-shaped wall frame within the gallery that tells us at once that these images are temporarily on show in this place. The temporary structure is like a half-made wall intimating a house, perhaps, that was never completed.

My mother would end up walking into the North Sea, her final act in a series of events that came to sum up her final few months of life. Somehow torn between her native Germany and Wales, where I grew up, her apparent suicide was located in equidistance from both these places, the symbolic nature of which is still the stuff of mystery.”

Peter Watkins

The is a clue about The Unforgetting and the enigmatic quality of work that evidences Watkins’ search for his lost mother, Ute, and – by implication – the lost child he became on her death. The child he was who shared his life with her is as uncertain as his memories, as elusive as the unconscious. He was there and yet his thereness, when she was alive, is fragile in ways the objects he depicts are not.

Ute Watkins’ final known actions are that she walked from the beach at the Dutch resort of Zandvoort into the North Sea on 15th February 1993. On the wall adjacent to the long wooden frame structure that encompasses most of the images is a black glass covered frame.You have to peer carefully through the dark glass to make it out. It holds an envelope on its side. You must turn your head sideways to read:

PHOTO OF UTE

FROM DUTCH POLICE

FEB ’93

The objects presented in The Unforgetting are not the stuff of mystery but rather suggest the stark, scientific quality of scene-of-crime evidence: an axe in a piece of wood with a small black and white photograph of a young man (Peter Watkins’ grandfather) resting against the blade, a photograph of a half-cut log held up by a human hand against a white screen. But it is in a domestic setting (in the background we can see a large window shrouded in a net, a hint of sunlight on a building opposite; in the foreground, a cover thrown over a settee to the left, an edge of carpet, a teapot, a table etc.,) In another work there are four glass goblets, one lying on its side in front of the others like a warning that this fallen one is not for use any more. There is an image of three spools of film, with just one slightly unravelling – a suggestion that there are so many images, memories and questions to come.

In the image we first encounter on entering the gallery, a set of ten books seem suspended in mid-air (divorced from any domestic setting) with a human hand that holds (or resists) the books, positioned at an improbable angle. The artist has a relationship with these objects but it is a relationship of questions, and absences.

Watkins made choices about this book collection and we, as observers, make our own connections. We assume these books belonged to the unforgotten one, or at least shared the space in which she lived. The small library contains examples of various narratives and ways of accounting for human existence through individual lived lives – from diaries to biographies, short stories and novels. The first is Lord Riddell’s More Things That Matter, a popular inter-war book of diaries, then Ernest Hemingway’s short-story collection, Men Without Women next to Anna Karenina, the book that Tolstoy considered his first true novel. There is a volume by, or about, Dostoyevsky, a writer most noted for his concerns with psychology and philosophy. The largest volume is H.G.Wells’ An Experiment in Autobiography. Next is the only paperback in this collection carrying the word “Deutschland,” an acknowledgement of Ute’s homeland. The remaining books are Dickens’ Great Expectations, Samuel Butler’s The Way of All Flesh, Balzac’s 1837 novel – César Birotteau from his series La Comedie Humaine; with the final volume being Samuel Pepys’ Diaries. This image suggests a world of complexities with intimations of moral downfall through illicit relationships, or the desire to break away from the confines of domestic life (Anna Karenina’s infidelity, Birotteau’s gambling, Pip’s embarrassment about his origins). The titles in this small library suggest other stories – things that matter, men without women, experiment, autobiography, Deutschland, expectations, flesh. There are many possible narratives reflected in these bibliographic clues.

In another photograph we find a ghostly image of the christening gown, covered by a yellow film; this is the only element of colour in the exhibition and is reminiscent of the yellow cellophane sheets haberdashers used to use inside display windows for protecting fragile baby knitwear and delicate booties etc., from the sun. Ute was a child too, was vulnerable – wore this light, floating garment to receive a sacrament before she could speak. There may be a concern about placing this precious piece in a ‘shop window’ – so it is protected against touch, damage or the light of our gaze. It made me think of Cavafy’s line, from his prose-poem Garments:

I will preserve them with reverence and great sorrow.

There is only one depiction of the artists’s body here, although his physical bodily presence is shown in his head and shoulders (as a child) and in some other pieces. In his self-portrait After Cupping he sits in a chair in a studio space, his back to us, facing away from the camera, but we can see he has his eyes closed as though meditating. The shutter-release cable runs from the cuff of his left trouser leg and it reminds us that he is attached to something outside of the frame of the photograph – technical and umbilical – waiting to be animated by it. There are traces, from cupping, of circular bruises on his back that demonstrates a quest for healing.

There is no sentimentality here, only the search for the unknowable in small energies of discovery and love. As Peter Watkins acknowledges:

I think that there is so much that is unanswerable when you go out in some form of truth or authenticity in your past, something which I think we all feel compelled to do at some point in our lives. To make sense of the past is to attempt to ground our lives, to afford it meaning and a sense of deep-rootedness, even if it’s painful to go in search of this.

Pauline Rowe, 2016

With thanks to Peter and to Open Eye Gallery who provided the opportunity for his interview, & thanks to the University of Liverpool.